At the beginning of 2015 I experimented by bringing in a new unit into my level 2 classical studies course. It was on the analysis of sacred texts & we focused on the theme of evil, more specifically demonology. We examined The Vendidad a sacred text of the Zoroastrian faith, which, of course, has some nice meaningful connections to the classical world. I used it as a scaffolding unit to teach students core skills & processes (as this is the first year level for classics). It also set the tone of using difficult primary sources & demonstrating the variety of secondary interpretations of historical evidence.

The previous year I made a goal to try & bring more elements of ‘fun’ into learning. I started to do that thing that I do when I am thinking about something. I read widely, casually participated in some mooc courses, & sought out resources for inspiration. The problem with game elements is that they tend to appeal to extrinsic motivation (though a recent literature review indicated that the right extrinsic motivators can lead to strong intrinsic motivation). Badges, points, silly little icons. These are things that marketing departments love. Am I a marketer? In the yearly drive of subject snake oil salesman ship to recruit sufficient numbers for classes I have been successful. Can I use such manipulative schools for enticing reluctant learners into learning or increasing the engagement of many learners in my classes.

I decided that on the one hand whatever was done needed to be done with purpose. On the other hand, I would probably only know if it works successfully if I try it. In that demonology unit it started with a hook. Drawing the students in with a ‘demon-hunter’ type of vibe & drawing on scenes from Supernatural, students were interested. At the time I remember it being fun but I dismissed its significance. Until the end of the year. All of those student voice & reviews & looking to the future & things turned out that this made a lasting impression for many students. This prompted me to undertake conversations with the classes about how we could productively expand this.

Game-based learning & gamification are complex & diverse topics with limited authoritative research. Most of the examples I come across as a gimmick or are designed by marketers to lull you in: collect these points & badgers. Now, I am not above using such tacky ploys if they can be used in a way that meet my learning goals.

So I started with the idea of a theme, The Inquistion of the Damned. This theme would colour the dynamics of my inquiry approaches. So I took the four key elements (inquiry, tools, context, & action) of my resourcing & put connected them into my theme. The theme came naturally out of the demonology concept & sought to extend it to encompass revealing the mysteries of elements from the entire classical world.

1: Inquiry

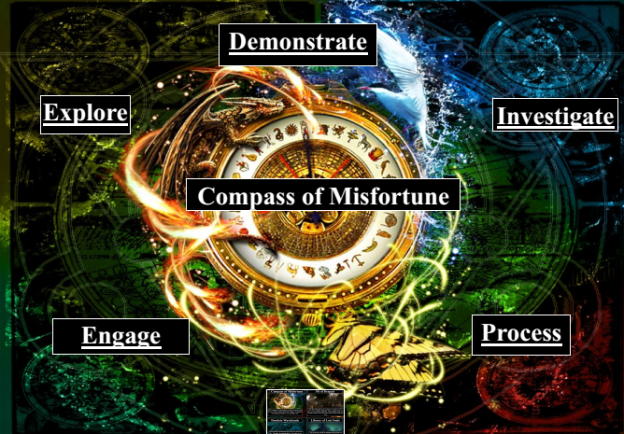

In my model, Inquiry has always been like a compass. Not something that you follow like a flow chart but something that acts as a means of direction. I don’t much care for arrows & things. I always feel that with an arrow, they are just giving me something to rebel against. I would not argue that this is complete or a definitive model or a model that will work for others.

The elements of this model came from my dissatisfaction in finding an inquiry model that was right for me & my approaches (& no arrows). In a future post I will take some time to delineate the details of this inquiry process.

2: Tools

Connected to inquiry is a series of skill areas & resources I have developed on key things like analysing source or writing. I see these as skills that are developed through training. The idea of ‘The Learning Pit’ is prominent in the Stonefields model, where failure or being stuck is OK & you develop strategies to get out. Drawing on Dante’s Inferno as something that tied in with the development of my theme came the Pit of Despair. Here there are different circles/arenas for training to up skill before continuing to progress through inquiry. The next stage is to complete the construction of a formal toolbox of weapons that can be used to train with.

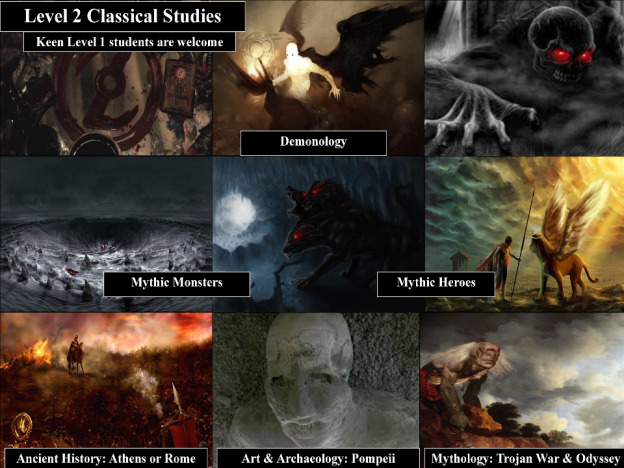

3: Context

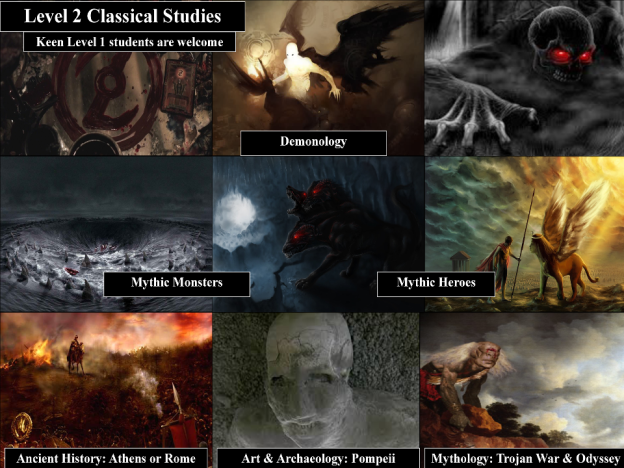

The other important element is the context that I impose or we co-construct. I don’t particularly care if students are learning about Virgil or Ovid or Alexander of Augustus (though Alexander & Ovid are my favourites), but I do care that they are engaging with a context that is appropriately challenging & will add cultural capital to their base. In addition to traditional topics, I also encourage exploration of more traditional topics like Socrates & philosophy or occultism. I believe a balance between the student choice & teacher imposition is where I currently reside.

While this is not an exhaustive list of the various topics, these are the main areas which I have explicit resourcing to support student inquiry. Students who have demonstrated sufficient autodidact skills are able to break out or negotiate a different context. I do not believe it is sufficient to merely say here is some Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus, & Justin go forth & become Alexander experts (though some can). Learners need a critical frame of reference & supporting resources (whether critical questions, narratives, or explanation).

4 Action

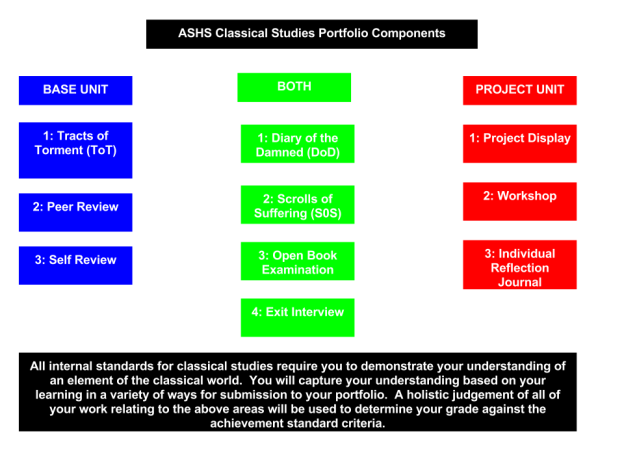

The last of the four key components are our primary methods of evidence collection. Diaries of the Damned focus on reflection processes; scrolls of suffering teacher-learner dialogue; spirit seance is collaborative actions; & tracts of torment are more formal types of submission.

In times gone past, I have had a problem with losing things for small periods of time in the cloud. Is the cloud so full that it will one day spit back acid rain of lost google docs down upon us? To overcome this challenge, thinking about my gamified theme, the idea of a status hub. Many prestigious organizations have a personnel file, no doubt criminals do too, not that these are mutually exclusive. With this, I can navigate through a whole class on a single web page.

In the next segment I will go into more detail about the development of rank & specializations.

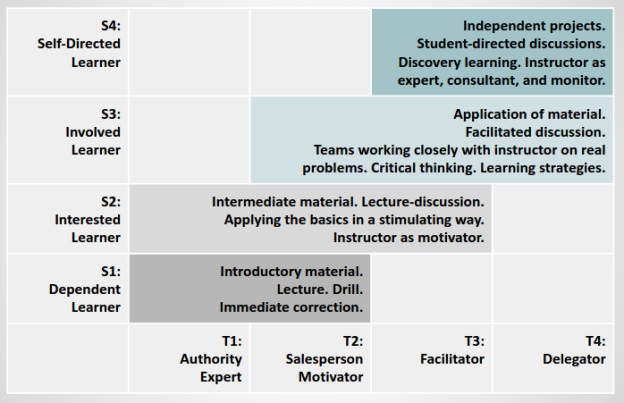

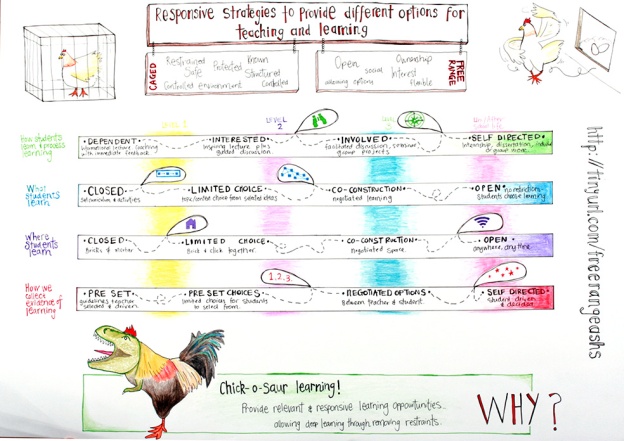

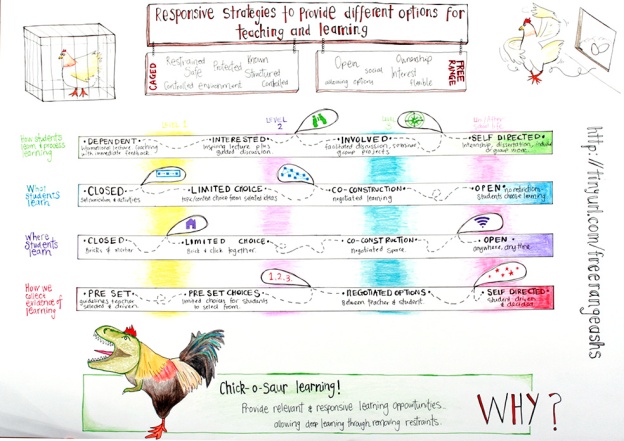

So we focused on how, where, what, & evidence collection. We focused on a spectrum model to encourage experimentation. Working with seniors, it is our responsibility to prepare them for life-long learning & the types of andragogical approaches towards the right-hand side of the scale. This was a progression approach. This is what I wanted to work towards but the limitations of appropriate external contexts & cultural capital still sat in the back of my mind. These things are important aren’t they? Really, they are not. Who am I to say that Ovid is more important than Virgil? Or that we shouldn’t study Aristophanes but Alexander the Great. I still stand strongly against the teaching of stupid pots (Greek vases).

So we focused on how, where, what, & evidence collection. We focused on a spectrum model to encourage experimentation. Working with seniors, it is our responsibility to prepare them for life-long learning & the types of andragogical approaches towards the right-hand side of the scale. This was a progression approach. This is what I wanted to work towards but the limitations of appropriate external contexts & cultural capital still sat in the back of my mind. These things are important aren’t they? Really, they are not. Who am I to say that Ovid is more important than Virgil? Or that we shouldn’t study Aristophanes but Alexander the Great. I still stand strongly against the teaching of stupid pots (Greek vases).